Ink, Irony, and the American Eye: A (Very) Brief History of

Political Cartoons

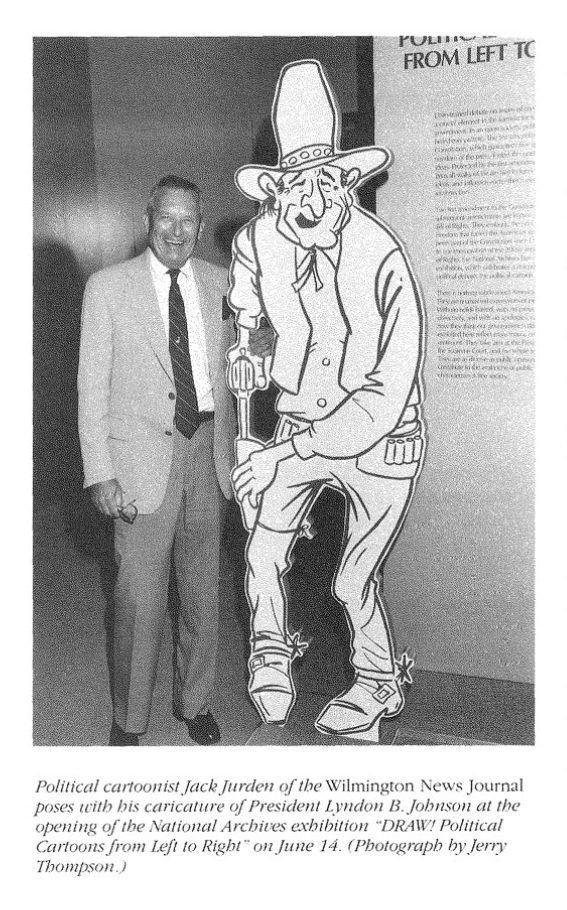

Nearly 35 years ago, I worked on a museum exhibit that explored the cultural influence and reach of political cartoons. The National Archives hosted the exhibit “Draw! Political Cartoons from Left to Right” starting in 1991, which celebrated American political cartoons and their role in public discourse, as noted in their annual reports from 1991.

The exhibit company that I worked for produced and installed the exhibit. At a time from before large scale digital graphics have become widely used throughout the industry, we silkscreened all the text and background imagery on large painted panels. Hand drawn political cartoons were scanned, enlarged, and turned into photo stencils to serve as a kind of supergraphic to fit the many panels that lined the curved walls of the Circular Gallery.

Political cartoons have been part of the American conversation almost from the beginning. Long before radio, television, or the internet, these drawings carried arguments, insults, warnings, and humor directly to the public. Benjamin Franklin’s “Join, or Die” snake, published in 1754, is often cited as the starting point—not just of political cartooning in America, but of visual persuasion as a civic act. From the outset, cartoons were not decorative; they were meant to persuade, provoke, and occasionally unsettle.

The late eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries now feel, in hindsight, like the glory days of political cartooning. As literacy expanded and printing technology improved, newspapers multiplied at an astonishing rate. From a few hundred papers in the early 1800s, the country grew to thousands by the Civil War and beyond. Editorial pages became expected reading, and political cartoons claimed a permanent place there—bold, unavoidable, and often memorable long after the day’s headlines were forgotten.

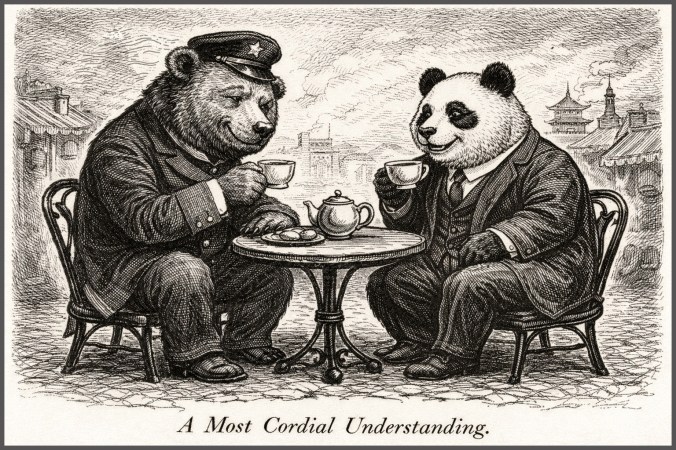

A Most Cordial Understanding is my first shot at a cartoon in the early style of 1840s Punch Magazine. It is very much in the Punch sweet spot: Polite on its face, slightly smug in tone, faintly ominous once you sit with it. We get a sense of two “respectable” powers conducting business as usual over tea; when paired with the recent pronouncements regarding Greenland, one can only wonder what they are really thinking.

This era produced giants whose influence still lingers. Thomas Nast’s crusade against Tammany Hall corruption helped bring down Boss Tweed and left us with the elephant and donkey as enduring political symbols. Others followed—Homer Davenport, John T. McCutcheon, Rollin Kirby—each shaping how Americans learned to “read” politics visually. Their drawings assumed patience and attention. They asked readers to stop, look, and think.

One of my favorites, Pat Oliphant stands out as one of the last great heirs to that lineage. His cartoons were spare, sharply drawn, and unsparing in their judgment. Presidents, generals, and bureaucrats were rendered slightly ridiculous, sometimes cruelly so, and always human. Oliphant’s recurring penguin—part conscience, part heckler—gave voice to public skepticism with a wit that felt earned rather than manufactured. Polite on its face. Slightly smug in tone.

What distinguished Oliphant’s work was its confidence in the medium. A single image, printed once a day, was enough. It didn’t need a monologue, a laugh track, or a follow-up explanation. You encountered it over coffee, folded into the paper, and it stayed with you. His cartoons were meant to be revisited, clipped, argued over, and remembered.

That world has largely disappeared. As newspapers have closed or shrunk, so too has the space for daily editorial cartooning. Political commentary has not vanished, but it has migrated. Memes flash by in seconds, optimized for recognition and outrage. Late-night television hosts and podcast personalities deliver satire in real time—often smart, often funny, but designed for immediacy rather than endurance. The encounter is louder, faster, and easier to share, but also easier to forget.

This shift doesn’t signal a decline in political engagement so much as a change in how it is experienced. Where cartoonists like Oliphant trusted silence and reflection, modern satire thrives on performance and momentum. Where cartoons once surprised readers on the editorial page, today’s commentary must be sought out, subscribed to, and algorithmically reinforced.

Looking back—through exhibitions like “Draw: Political Cartoons from Left to Right,” and through the artifacts that remain—it’s tempting to see that earlier period as a high point. Not because it was more civil or more virtuous, but because it trusted the reader. It trusted that a drawing could carry an idea, that ambiguity had value, and that satire could linger. In an age of endless commentary, the old cartoons remind us of the power of ink, restraint, and a moment of pause.

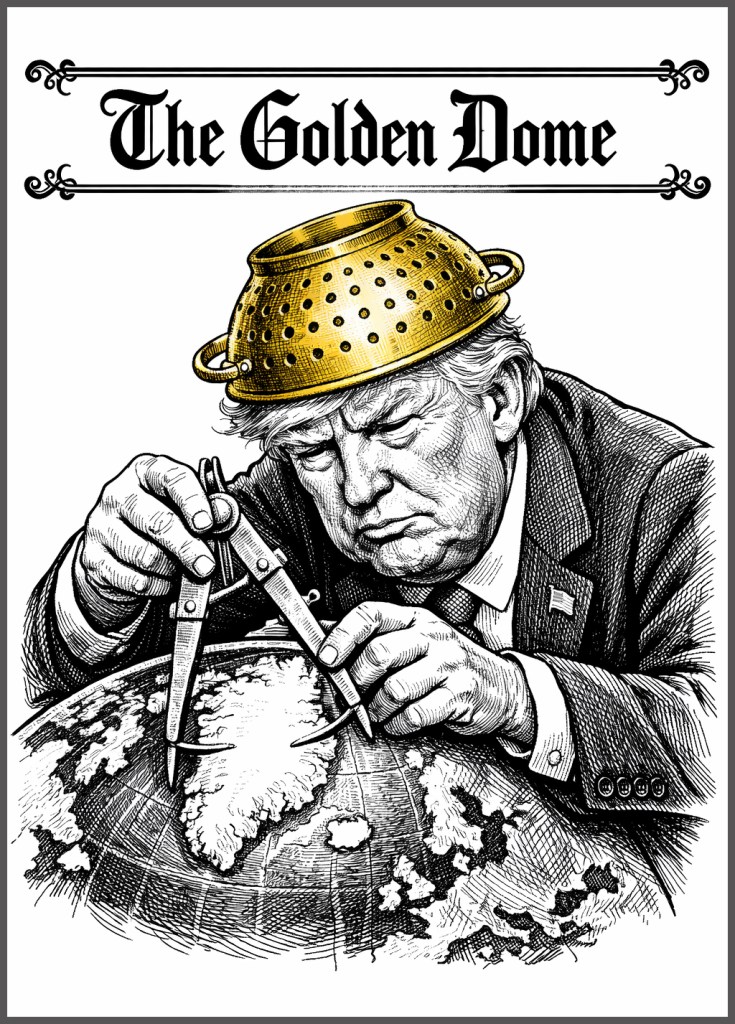

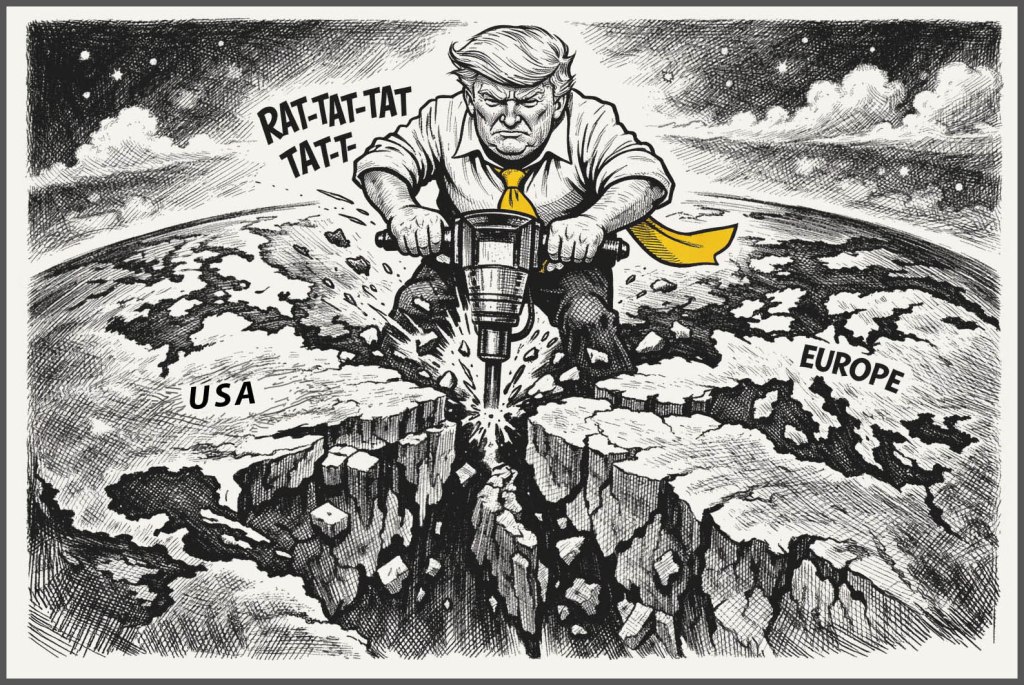

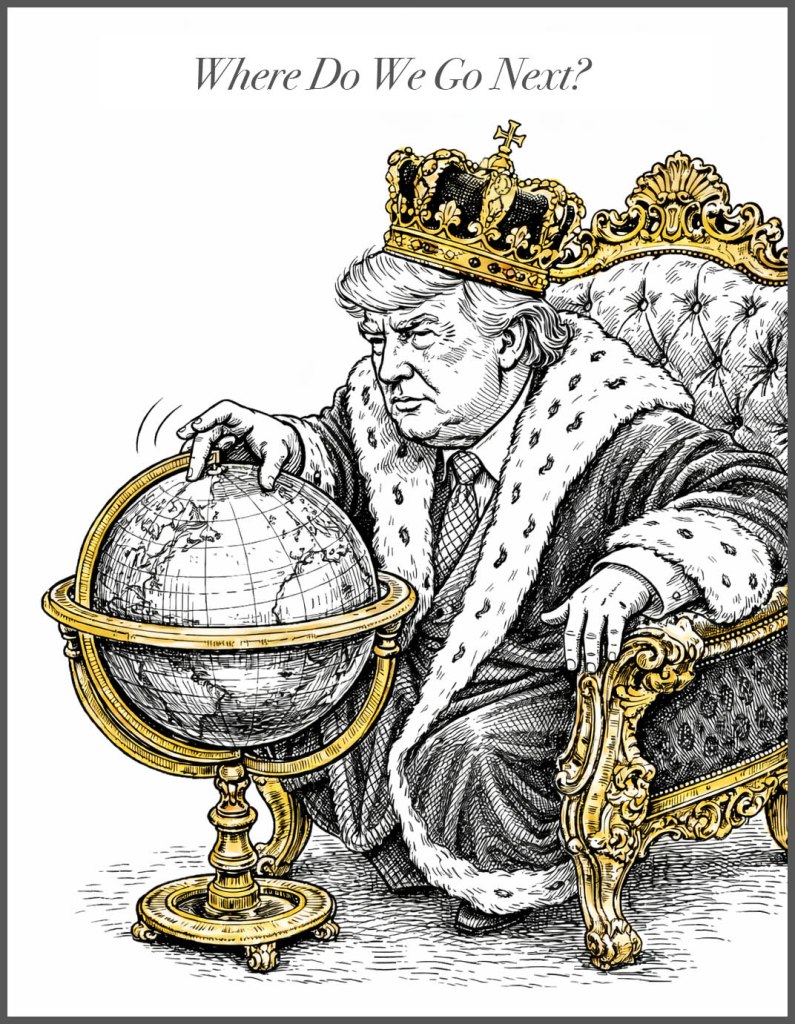

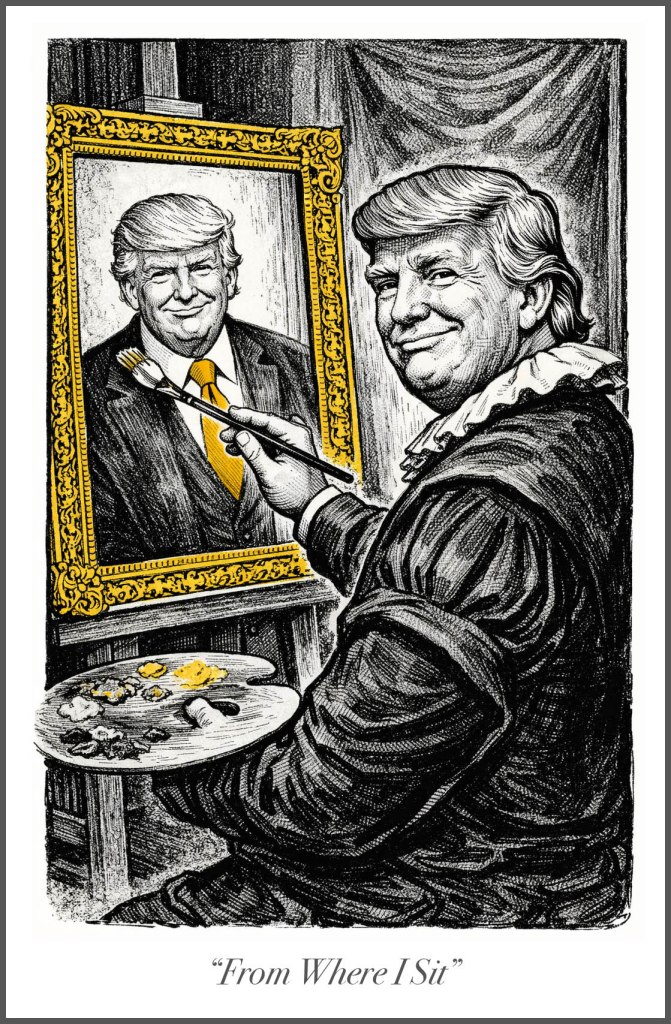

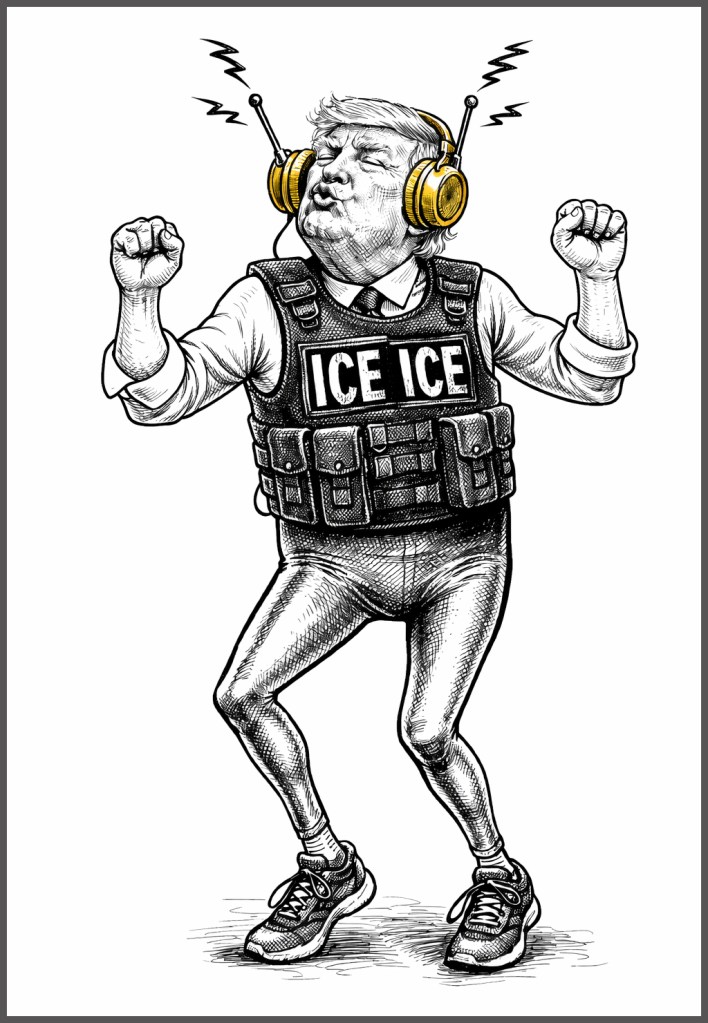

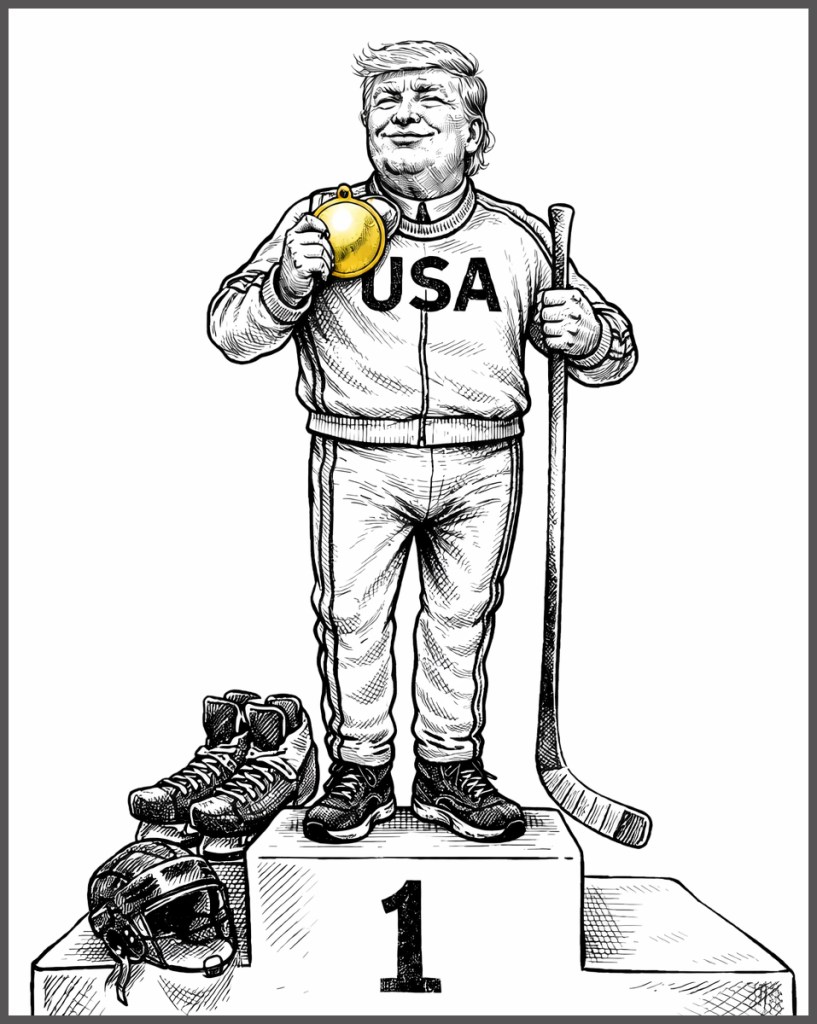

Below are a series of cartoons I’ve created over the past few weeks that incorporate that sense of urgency compiled with a mix of wry humor or satire. I’ve been using the considerable skills of ChatGPT augmented with my own perspective of the times in which we live. For good or ill, we find our country at a very troubling crossroads. I might not get out and walk in protest as I once did; it doesn’t mean I like what’s happening and am planning on remaining silent. Quiet maybe, but not silent.